Health

How a toxin from the gut microbiome may help spark colorectal cancer

Getty Images

Findings suggest colibactin may be promising target for disease prevention

For years, a mysterious bacterial toxin lurking in the human gut was suspected of driving colorectal cancer. Now researchers in a pair of Harvard labs have caught the toxin in the act of damaging DNA and creating the very sorts of mutations long implicated in the disease.

The new study, published Thursday in Science, is the first to detail the structure of the DNA lesion formed by colibactin, a natural product toxin made by common gut bacteria. Leading the research team were Emily Balskus in the Department of Chemistry and Chemical Biology and Victoria D’Souza in Molecular and Cellular Biology.

“This molecule has been really challenging to study because it’s very chemically unstable,” said Balskus, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of Chemistry.

The findings, enabled by National Institutes of Health funding that was terminated and later restored, suggest colibactin may be a promising target for prevention of the deadly disease.

The major form of DNA in our cells is a double helix: two strands twisted together. Many carcinogens damage one strand or the other, but colibactin does something more extreme — it creates a cross-link.

“An inter-strand cross-link means that your DNA-damaging agent reacts with both strands of DNA,” Balskus said. “It links the two strands of DNA together, creating a particularly toxic form of DNA damage to the cell.”

This kind of a lesion can lead to broken chromosomes, faulty repair, and potentially cancer‑causing mutations.

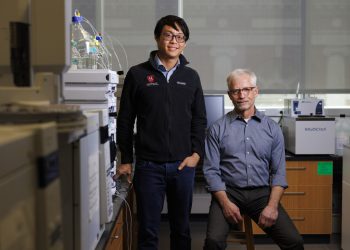

Victoria D’Souza (left) and Emily Balskus.

Credit: MCB

“Every time the cell is trying to make a DNA copy out of its genome, it needs to unwind the two strands,” said D’Souza, professor of molecular and cellular biology. “The cross-link causes a major hurdle for replication.”

The study was produced in collaboration with scientists Peter Villalta and Silvia Balbo at the University of Minnesota. The Harvard team also included Erik S. Carlson, a former postdoctoral fellow in Balskus’ lab, as well as graduate students Raphael Haslecker and Linda Honaker in D’Souza’s Lab and Miguel A. Aguilar Ramos from the Balskus Lab.

The researchers began by asking a deceptively simple question: Does colibactin cross-link any DNA sequence it encounters, or does it have favorite spots?

Colibactin is a toxin that is made by certain strains of E. coli and other gut bacteria that carry a biosynthetic gene cluster known as pks or clb. Because the compound falls apart quickly, the team had to produce colibactin using living bacteria to make it in situ for all their experiments.

These colibactin‑producing bacteria were used to generate the toxin directly in the presence of short pieces of DNA. The researchers then measured where cross-links formed, leaning on classical gel‑based sequencing as well as mass spectrometry with their collaborators from the University of Minnesota.

They found colibactin has a strong preference for cross-linking stretches of DNA built mostly from adenine (A) and thymine (T). Understanding that preference required shifting into structural biology, so D’Souza’s lab used nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to build a structural model of the lesion.

“I think the biggest hurdle for solving a structure by NMR is the need for a lot of material,” D’Souza said. “The team was able to produce enough and overcome that major challenge.”

The resulting structure explains why colibactin is so picky. AT‑rich segments of DNA have a minor groove — the narrow channel on one side of the helix — that is tighter and more negatively charged than in other sequences.

“The cool thing about colibactin is that it perfectly fit in terms of shape and charge complementarity,” D’Souza said.

These molecular details strengthen the case for further investigating the links between colibactin‑producing bacteria and colorectal cancer. Exposure to colibactin was known to generate mutations at the AT-rich sequences in the genome. Understanding colibactin’s specificity now explains the locations of these mutations, which have been detected in colorectal cancers.

Notably, the specific mutations attributed to colibactin are enriched in tumors from younger patients. It turns out that E. coli — the main colibactin producers — are most abundant in the infant gut microbiome. That lines up with the early‑life window when environmental risk factors for early‑onset colorectal cancer are thought to act.

The findings highlight the power of cross‑department collaboration, researcher say.

“When a project is as difficult as colibactin has been, you can’t expect one group to have all the expertise that’s needed to solve problems,” Balskus said. “At Harvard, we’ve benefited so much from having great access to experts across a wide range of different disciplines.”